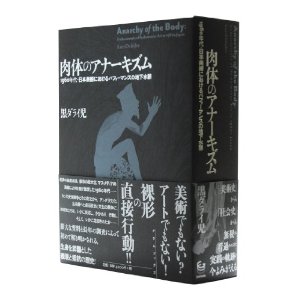

Awarded 2010 Art Encouragement Prizes by Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs

Written by Kuroda Raije

768 pg.

4,200 JPY tax excluded ![]()

<Important>Announcement of Planned Release for Expanded and Revised Edition (Tentative)

The book is currently out of print, but we plan to publish an expanded and revised edition (tentative) by the end of 2026. We will announce the specific release date once it is finalized.

<Overview of the Book>

The history of Japanese art of the 1960s has often been introduced in exhibitions and

discussed, due to bold experiments carried out by the artists and the dynamic evolution of art from

Informel painting to Anti-art, followed by technology art, Mono-ha and conceptual art. However,

the exhibitions and writings on the history of this period have typically ignored the performances of

visual artists, except those by Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai [Gutai Art Association] and Hi-Red Center.

In fact, many other artists also ventured out of the context of ‘art’ to do performances in public

spaces throughout the 1960s, which represented the anti-institutional culture of the time more than

any other works and performances already recorded in history as the mainstream of the

‘contemporary’ art.

This book examines performances of obscure artists in order to place them in the cultural

and political history of the anarchist tendencies of that epoque, which also manifested themselves

in the contemporary counter-culture and political activism. These performances took place in the

context of the Anpo Struggle (Movement against Japan-US Security Treaty) in the early 60s, and

Zenkyoto (All-Student Joint Struggle Conference) movements in the late 60s, as the artists took

part in the protests against the contemporary social ideals and rapid modernization.

The book is divided into four sections. In Section 1, we examine the significance of the

history of performance arts in Japan, demonstrating why it has been neglected in art historical

research that relied on the fabricated mainstream and remaining works while admiring ‘high’ art in

‘international’ style. The performance art discussed here was actually an inevitable result of

‘Anti-art’ shown at the Yomiuri Independent Exhibitions in early 60s. To transcend a premature

end of the 1964 debates on ‘Anti-art’ which were confined to an ‘art world’ that overly referred to

foreign trends, we need to expand the concept of ‘Anti-art’ to reflect the secularity of everyday

reality caught in the old-fashioned life style, while also taking the new phenomena into

consideration— the spread of urbanization and omnipresence of the mass media.

In Section 2, we chronologically retrace the history of Japanese performance art from 1957

to 1970, as viewed from this new perspective. Performance art started as a public demonstration

of action painting popularized by Georges Mathieu in 1957, which stimulated Shinohara Ushio to

start presentations of artist’s personality in mass media. Around the same time, Kazakura Sho did

his first performance independent from painting as a challenge to theatrical conventions. This

move toward bodily presence and ‘direct action’ was accelerated by the suppressed energy and the

anarchist tendencies after the defeat of Anpo Movement in 1960.

After the Yomiuri Independent Exhibition was suspended in 1963, with Japan embarking

upon its phenomenal economical growth, performance art spread to regional cities and streets out

of the narrow art/gallery confines, as seen in the early experiments by Zero Jigen (Zero Dimention),

and shows such as Gifu Independent Exhibition in 1965, which led to creation of a network of

artists living in remote areas. Joint performance art shows started also in 1962-64.

In 1966- 68 when angura culture bloomed, more artists started performances on streets and

stages for popular audiences, both individually and collectively, such as Kurohata, Mizukami Jun,

Koyama Tetsuo, and Kokuin. In Kansai (Kobe, Osaka, and Kyoto), The Play was founded in

1967 with Mizukami and Ikemizu Keiichi et al., as a group for collective projects. In 1968-69, The

Play combined the spontaneous/simultaneous performances of individuals with the organized,

collective performances of groups.

When the countdown for the opening of Expo ‘70 started, many of the avant-garde artists as

well as architects, designers, and musicians were invited to contribute to this national event,

following the spread of ‘inter-media’ events after mid-1960s. As a response, the ‘ritual’

performance artists succeeding the Anti-art tendencies formed Banpaku Hakai Kyoto-ha [Expo’70

Destruction Joint-Struggle Group] in early 1969, aiming to ‘smash’ the Expo’70 by organizing

events protesting against the societal brainwashing that advocated economic and technological

progress and was promulgated by the government and big enterprises. However, after the leading

members were arrested under the massive police crackdown on activists and hippies in the streets,

the group self-dissolved, and its members headed off in various directions.

In Section 3, we focus on artists and collectives that played important roles in the history of

performance art in 1960s, examining specific developments not addressed in Section 2. Here we

discuss Kyushu-ha [Kyushu School] (Fukuoka), Asai Masuo (Seto), Zero Jigen [Zero Dimension]

(Nagoya/Tokyo), Kurohata [Black Flag] (Tokyo), Koyama Tetsuo (Tokyo), Kokuin [Announcing

Negative] (Tokyo), solo woman performers, Itoi Kanji (Tokyo/Sendai), and Shudan Kumo [Spider

Collective] (Fukuoka).

Finally, in Section 4, we delineate the cultural, social, and political backgrounds of the

aforementioned numerous performances and evaluate the performances as the artists’ continuous

protest against the elite culture, economic and technological modernization, the increasingly

urbanized but also a more controlled society, and the conventional style of leftist movements, with

the adventurous spirit of ‘Anarchy of the Body’.